The UK finance sector’s new Consumer Duty regulation is now in force, as of 31st July 2023. Its game-changing mandate is to make all regulated finance firms ‘act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers’. So why do all finance businesses need to give serious thought about friction in their system, service and product design?

In previous articles, we’ve looked at how firms can comply with the Duty with Service Design thinking, how the Duty requires good outcomes for all customers including those vulnerable to financial harm, and what designing through that lens of vulnerability looks like in practice: an approach any business wanting to deliver brilliant customer experiences should consider.

Consumer Duty compliance is about strategy, not box-ticking

Yet countless fintech articles and keynotes we’ve seen this summer about Consumer Duty AI tools and other out-of-the-box software solutions seem to be missing a critical point: meeting the Duty isn’t about box-ticking to achieve ‘compliance’.

Compliance is the side effect of making the necessary shifts – mindset, cultural, behavioural, technological – to achieve those ‘good outcomes’ and create a win-win for both the firm and its customers. A situation where finance firms don’t make their profits at the expense of their customers, as per the PPI mis-selling and payday loans scandals. The Duty, in effect, says if finance firms can only sustain operations if customers lose out and don’t achieve their financial objectives, they won’t be compliant and shouldn’t be operating. And there's no digital quick fixes that can deliver that.

Customer-centricity isn’t enough for Consumer Duty compliance – or sustainable business

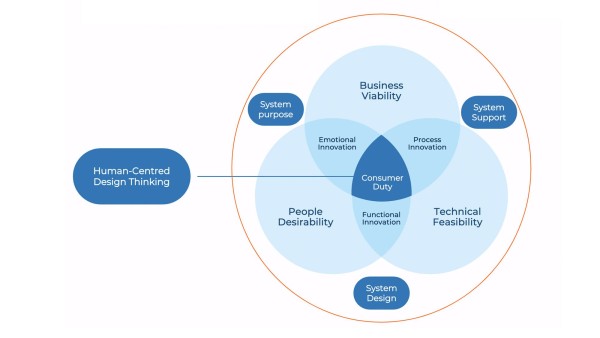

It means Consumer Duty can’t just be about customer-centricity. This is a challenge for banks and fintechs, who are rightly proud of shaking up the legacy finance sector with fast, frictionless, brilliant CX design and speedy onboarding with improved KYC and AML processes. While designing and delivering products, services and experiences to deliver customer satisfaction, loyalty and brand advocacy is great, it won’t necessarily result in ‘good outcomes’ as the FCA defines them.

In recent years, speed and friction-reduction has been everything - understandably so. Legacy financial processes were complex and full of pain-points. Services were only open during work hours in the work week, or it would take weeks to get an appointment to discuss a loan application. And while traditional bank managers and brokers had personal knowledge of customers’ circumstances to deliver great experiences, it could also come with bias or paternalism. All of this could be helped by digital services and data-led, automated decision making.

So, firms’ product and marketing teams have been ruthlessly focused on online: reducing the number of clicks required to purchase a product, on-boarding times and drop-out rates, resulting in extreme streamlining of processes to achieve high conversion rates. To an extent, this has been a great thing. Card payments can take one to three days to transfer funds, whereas today’s Payment Initiation Services built on open banking APIs can transact in mere seconds.

Yet even if a customer enjoys every single bit of a friction-free, fast experience with an innovative financial product or service, if the end outcome is that they can’t pursue their financial objectives, come away out of pocket, or are even harmed in a way that the finance business could reasonably have anticipated, thenthat firm won’t be Consumer Duty compliant - customer-centricity or not.

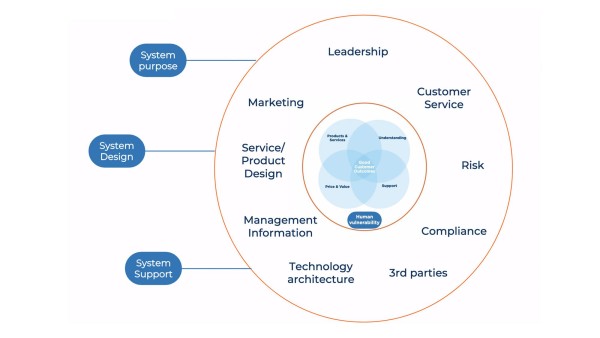

And, critically, it’s not sustainable. Design thinking success occurs when a company’s entire system is set up to be what I call Loved, Lean and Lucrative (Desirable, Feasible and Viable in IDEO’s famous terminology). When Consumer Duty’s good outcomes are now at the centre of the system, sustainability is not just about making profit for the business but also delivering value (and not harm) to the customer.

The customer harms involved in low-friction finance

There have been some devastating preventable harms due to low-friction finance offerings. In the US, a 20-year-old committed suicide after the Robinhood trading app - infamous for its gamification - indicated he was (erroneously) $730k in the red after the platform approved him to trade high-risk Options without sufficient explanation or even a way to communicate with the platform. The Financial Industrial Regulatory Authority (FINRA) accused Robinhood of giving customers “false or misleading information” and had “failed to exercise due diligence” before approving customers to trade Options.

In the UK, such friction-free gamification is causing similar concerns about gambling-type behaviours. The FCA Financial Lives Survey 2022 surveyed 3,000 consumers across five investing apps. In three of the five, nearly a quarter of customers were demonstrating ‘at-risk’ behaviours. Nearly 1 in 10 (9%) of adults with investments had borrowed money in order to fulfil the investment, and nearly half (49%) of these would not have been able to make the investment without doing so.

In a case more close to home, I’ve seen cases of vulnerable borrowers receiving unaffordable same-day and longer-term loans in just few clicks, from lenders who can clearly see repayment is impossible without taking on yet more high-interest debt. This predatory practice ensnares people in vicious cycles of spiralling fees and penalties, causing severe financial and emotional damage. Approval of such loans represents an egregious failure of duty of care, prioritising profit over the welfare of struggling consumers. This is in direct conflict with the ethos of Consumer Duty.

Low-friction finance can also harm firms

It’s clear that the very same characteristics of fast customer onboarding and friction-free products and services also increase risks to finance firms themselves.

Authorised Push Payments (APP) now make up around 50% of the UK’s £1.2bn financial fraud losses, of which 78% originate online. APP scams victims into making large money or asset transfers to fraudsters. And that’s not about digital literacy or age. Younger age groups are more likely to be affected due to their greater usage of digital finance. People aged 20-29 report the most instances of criminal activity (82.2K), followed closely by those aged 30-39 with 80.9K reports.

The problematic nature of ‘one or two clicks and done’ payment is now being tackled by new recommendations from the Payments Systems Regulator; an implicit threat the PSR will make reimbursement mandatory for fraud victims. Firms will need to adopt stronger fraud measures, likely adding in friction to not end up out of pocket. Similarly, weighty FCA fines are mounting up due to Anti-Money Laundering (AML) breaches for both legacy finance and fintech firms firms due to failures in onboarding in KYC, AML and PEP processes.

AI and machine learning tools are often mooted as the solution to these types of issue, “providing effective and robust fraud and AML checks in real-time, and as such, have no impact in the broader customer journey”. But add to that the Consumer Duty’s extra requirements to deliver good outcomes for all customers, influenced by deeply human circumstances like bereavement, mental health, disability and literacy, and it becomes clear that automation, AI and the ‘faster is better’ mentality can’t provide the sole answer.

Doing finance faster makes sustainability harder

In essence, the quicker and less complex any finance process is, the more likely it is that harms can happen to both parties. That could be fraud, default on payments due to unsuitability for a product, or simply lower customer Lifetime Value (LTV) by swiftly onboarding the wrong type of customer.

The latter is particularly acute when we look at the concept of systems needing to be Loved, Lean and Lucrative to be sustainable. Viewed that way it’s understandable why by 2022, only 5% of neobanks (like Revolut and Monzo) had broken even. Of course, fintech startups are designed to be growth engines, not immediately profitable. But one reason they aren’t yet financially Lucrative, even as they are Loved and Lean, is because of their high customer acquisition cost (CAC) due to offering lower fees and free services to attract new customers. This is exacerbated by lower margin products, more limited product offerings and onboarding lower value customers, who they can’t afford to lose since customer numbers and ‘churn rate’ are key investor metrics.

Reducing complexity and friction in customer acquisition can only go so far. To be truly sustainable, you need a focus on value propositions, higher value customers and offboarding lower value customers who are also not benefiting from the services. Again, it’s back to figuring out how to make it a win-win for both sides.

Positively introducing friction to finance design

The FCA makes it clear Consumer Duty isn’t about slowing financial services down for the sake of it. It’s about introducing the right level of friction at the appropriate moments to help the business and the customer think: is this product or service really suitable? And what potential good (or bad) value outcomes are going to result from this action?

The FCA’s Duty guidance to firms says:

“What amounts to appropriate friction or an unreasonable barrier will depend on the circumstances. We expect firms to apply judgement and be able to distinguish between positive frictions or nudges that support good outcomes and harmful frictions that create unreasonable barriers (sludge practices).”

Positive frictions might be additional steps for verification to prevent fraud, to put mechanisms in place that raise flags in the case of certain vulnerabilities, or to make customers aware of consequences of cancelling a contract early, for example. From the other side, negative friction is where consumers can’t switch provider or see prices to switch product even, can’t easily contact customer support (particularly common in pure digital fintech players) or can’t easily make a complaint.

The key is systems set up to be as fast as humanly and technologically possible, so that adding in positive friction doesn’t negatively impact the customer experience. It's about integrating disparate data sources and providing holistic decision-making insights. This allows designers to make decisions across the customer lifecycle and customer journeys, including supporting customers through periods of stress and difficult life events.

The need for a holistic, Systems Thinking approach

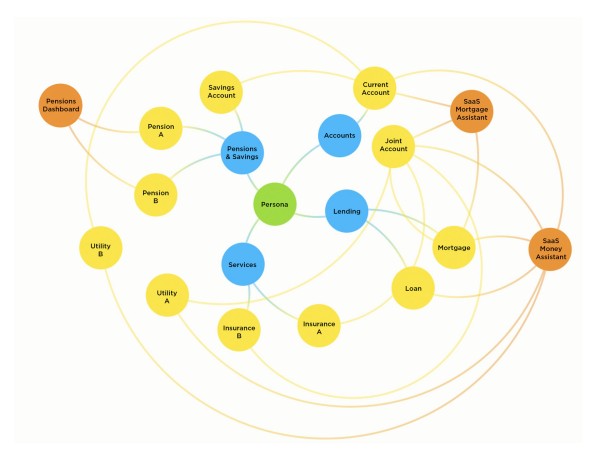

Finance firms often look at Consumer Duty from a pure Products and Service perspective, linear and in parallel: ‘the customer journey’, ‘the product lifecycle’ and seeing if those journeys and lifecycles are ‘compliant’. But people’s lives don’t flow in a linear parallel way. Signing up a customer to 10 individually well-designed products with 10 brilliantly designed customer journeys won’t guarantee a ‘good outcome’ when considered in the round. It certainly doesn’t capture a customer’s fuller financial ecosystem, beyond what can be captured by credit checks on a basic level.

This is also true from the customer perspective. Most people have a limited view of their financial situation in relation to the web of financial products and services they’re signed up to. How many people can definitively say they know exactly how much they are worth, what liabilities they have, how much can they really afford when you consider pay, pension, mortgage, student loans, shares, investments, ISAs, crypto and any other number of potential factors...?

One potential way to solve this almost game theory-type dilemma is with Open Banking. By allowing data and insight on customers to flow freely, it can support both finance firms and customers to gain a full understanding, and so achieve ‘good outcomes’ for both parties.

Let's look at my example of credit loans. The company just had a snapshot of that person in that moment in time within its own systems. All other external parties were just potential vendors and provisioners, not co-operative parts of a wider living ecosystem that could inform them of the person’s true situation. Assuming that the provider did want to abide by Consumer Duty requirements, if that Systems understanding and view had been in place, there would have been more friction, and the customer would have had the right information at the right time to hopefully make the right decisions.

More importantly, not only would it have produced a Consumer Duty compliant outcome, the risks to all involved would have been dramatically reduced. Back to the game theory: no big winner, no big loser, but more positive, sustainable outcomes for both sides.